“Blake … was … mad!”

This was Jonathan Wordsworth’s introduction to William Blake’s ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. A tall, patrician figure, with an air of amusement and a strong resemblance to his great-great-great-uncle, the poet William Wordsworth, Jonathan taught the Romantics during my second year at Oxford1.

At 21, I was far too afraid of my own madness to be drawn to Blake. These days, better acquainted with that madness, I feel differently. Blake’s ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ seems to me now not madness, but a species of weird fiction, expertly created to disturb the reader’s consciousness. The question is whether it does so to “salutory and medicinal” effect.

Blake’s work includes a story in which the narrator and an angel visit hell:

By degrees we beheld the infinite Abyss, fiery as the smoke of a burning city; beneath us at an immense distance was the sun, black but shining; round it were fiery tracks on which revolv’d vast spiders, crawling after their prey; which flew or rather swum in the infinite deep, in the the most terrific shapes of animals sprung from corruption; & the air was full of them, & seem’d composed of them; these are Devils, and are called Powers of the air. I now asked my companion which was my eternal lot? he said, between the black & white spiders.

‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, William Blake

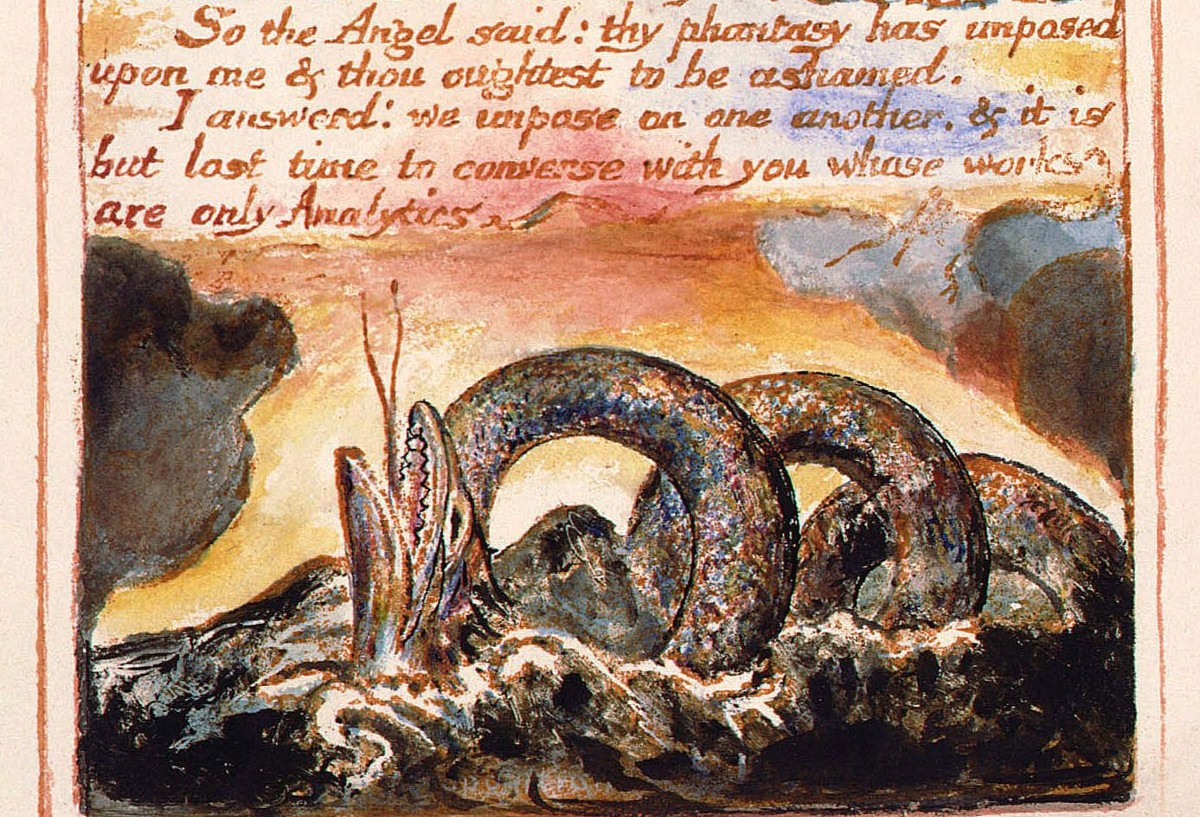

We glimpse at last the great beast Leviathan, ruling over all (above). Yet when the angel leaves, this horrific vision transforms into a moonlit pastoral scene by a river, with a harpist playing. The narrator then visits the angel and forces him to travel to heaven, a place of brick buildings where monkeys and baboons savagely cannibalise each other, and themselves.

So the angel said: thy phantasy has imposed upon me & thou oughtest to be ashamed.

I answer’d: we impose upon one another, & it is but lost time to converse with you whose works are only Analytics.

For Blake, the angels represent “reason” and the mind; while the devils are “desire” and the body. Here, he is in agreement with his older contemporary, the philosopher David Hume, who said, “reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions”. Hume showed that there was no logical basis for believing in causality, and that the entire edifice of scientific reason had its basis in superstition. And this is why for Blake the angel’s disembodied “Analytics” are only a partial view of life, and the lesser part at that.

Iain McGilchrist’s ‘The Master and His Emissary’ explores the science of the brain, and in particular the unfashionable question of why the brain is so deeply divided into two hemispheres. The answer seems to be that animals’ brains have to carry out two main functions simultaneously – as a bird has to peck at its food, while watching for danger all around. The radical division between the two hemispheres make this possible. In humans, the left hemisphere is concerned with focused attention, and the right on embodied relational awareness in the present moment. For McGilchrist, the “master” is the right hemisphere, while the “emissary” is the left; but in the modern world the left hemisphere has come to assume mastery, and to impose on us its mechanical, algorithmic, disembodied consciousness.

McGilchrist’s theory (he was originally another Oxford scholar of English Literature) fits well with Blake’s, speaking as it does of the struggle between an embodied intellect and a disembodied one. The old joke says that there are two kinds of people in the world: those that believe there are two kinds of people, and those that don’t. The angel’s analytics involve exactly this kind of division, between those who are going to hell, and those who belong in heaven; whereas Blake’s vision shows that heaven and hell are illusions created and imposed on others by our way of seeing, our “phantasy”. The angelic left-brain thinking follows the logic of “either / or”, while the hellish right brain offers us the Blakean “both – and”.

The vison of hell from the angel’s point of view is a powerful one, strangely reminiscent of the machine hell found in ‘The Matrix’ or the biomechanoid monsters from the ‘Alien’ movies. And yet, in the end, it is nothing but the distorted view of reality imposed by the angelic. The horror is no more than a failure of the imagination, and can be defeated by art, which restores our vision to wholeness. This wholeness is embodied and relational. We can only relate to others from an embodied presence, and not through the mind alone, working in isolation.

The most famous passage is worth quoting in full:

The ancient tradition that the world will be consumed in fire at the end of six thousand years is true, as I have heard from Hell.

For the cherub with his flaming sword is hereby commanded to leave his guard at the tree of life, and when he does, the whole creation will be consumed, and appear infinite, and holy whereas now it appears finite & corrupt.

This will come to pass by an improvement of sensual enjoyment.

But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul, is to be expunged: this I shall do, by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.

For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

The final words are well-known from Aldous Huxley’s account of his 1953 mescaline trip, ‘The Doors of Perception’, but they take on a fresh power in their full context. For Huxley psychedelics offered a glimpse of what he called “mind-at-large”, by shutting down the “reducing valve” of ordinary consciousness.

Blake’s “printing in the infernal method, by corrosives” is, however, a laborious, all-too-material task – dirty, inky, smelly, toxic, difficult. Blake’s description is inseparable from the craft of etching copper plates with acid, the method by which he made ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. There may be an important distinction here between art that is also craft – i.e. made, probably in a physical medium – and conceptual art. The latter evades the messiness, and also the fortunate creative error. Blake portrays himself here as a Miltonian Satan, striving with the means available in Hell to “expunge” “the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul”. He does this not by escaping the sensual world, but by intensifying its pleasures and suffering.

The angel said “thou oughtest to be ashamed”, which is always the argument presented by the angelic against embodied experience. Shakespeare drew on the related simile of the dyer’s hand when writing of his own experience of shame:

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

Sonnet 111

And almost thence my nature is subdu’d

To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand.

Pity me then and wish I were renew’d;

Blake, by contrast, will not be shamed. Unlike the Hells of Dante or Milton, Blake’s is not a place of punishment, but of unrepressed creative energy. We can trace the development of similar thoughts in psychotherapy through Freud’s Id (“It”), Wilhelm Reich’s understanding of libido, Arthur Janov’s Primal Therapy, and in Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing. These authors take different views on the wisdom of releasing such energies, but share an appreciation of their power and vitality. Blake, for whom “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”, is perhaps closest to Reich.

Another important therapeutic question is illuminated for me by Blake: the transference. It was Freud who first discovered that patients ‘transferred’ feelings and thoughts about other people in their lives – especially fathers and mothers – onto him. At first, Freud tried to minimise this disturbing effect, but he soon realised that the transference held the key to healing. What was to be avoided, however, was counter-transference, in which the analyst allowed their own personal pathology to infect the relationship.

Later generations of psychotherapists came to realise that the counter-transference was, in its turn, profoundly helpful, providing vital, felt insight through the embodied sense of what the patient experienced. Counter-transference could be resonant, where the therapist experienced what the patient did, or complementary, where the therapist held an equal and opposite feeling. The real danger now, however, was considered to be enactment, in which the unconscious of the therapist played out some hidden drama with the unconscious of the patient.

The reader will probably guess what happened next. During the past 40 years or so, enactment too has come to be recognised as therapeutic. For therapists who can allow themselves to participate in the client’s struggles, to the extent that there is no more attempt at objectivity but an acceptance that reality is intersubjective, the enactment is where the real transformation can take place2.

It is just as Blake said to the angel: our “phantasy … we impose upon one another” .

For all that conventional therapeutic approaches advocate ‘bracketing’ emotions, ‘professional boundaries’, being ‘clean’, not touching a client’s body, doing no harm, the truth is that to be effective, the therapy happens within a relational space that contains both (or all) parties, and all kinds of manifestations of embodied ‘hell’.

No therapeutic boundary can survive a synchronicity

While some might recoil from this, fearing “vicarious trauma”, or being drawn into some inappropriate and shameful relationship, the disconcerting truth is that we are already involved with each other – therapist and client – in weird and inexplicable ways. This goes far beyond sharing our feelings empathically through mirror neurons.

Our mutual involvement may not have a beginning or an end. Traditional Tibetan medicine taught the doctor to take note of what they might observe on the way to see the patient, thus acknowledging the divinatory aspect of healing. In my own practice I make use of Tarot cards. Phillip Carr-Gomm, who created the DruidCraft Tarot, said to me that the cards could be seen as “Seventy-eight archetypes that we cast into the air to reveal the hidden patterns of meaning”.

My friend, an occultist and psychotherapeutic counsellor, reported these words, from a client, “No therapeutic boundary can survive a synchronicity”. It’s the special function of synchronicities to melt away the apparent surfaces, revealing to us the network of meaningful connections that does the healing. In my talk to the Parapsychological Association, I explored how a dizzying series of synchronicities drew me inextricably into my client’s story over several of his past lifetimes. I don’t believe this is because I’m special. Not at all. Rather, it reveals the connections that hold us all and which will reveal themselves to us if we look deeply enough.

For Blake, the infernal medicine burned away the apparent surfaces between body and soul, revealing the infinity of the Real. This same principle can be applied to the weird craft of therapy. If we hold back from involvement with the apparent other – body, world, human, spirit, trauma, madness, suffering – fearing the loss of our angelic detachment and clarity, then we have “mere analytics” to offer. And the truths glimpsed in this way may be less absolutely truthful than we might imagine. Yet if we allow ourselves to be drawn into the same hell-bound whirlpool as the client, perhaps both we and they can survive it together.

1 Jonathan and I were not close. Yet in 2006 I picked up a copy of The Times newspaper in a London sandwich shop and, for no reason that I could identify, turned to the small-print death notices. There I read that Jonathan had just died.

2 I am grateful to Michael Soth for this account of transference, counter-transference and enactment.

Copyright © 2022 My Sunset by Bogdan Bendziukov.