In 1899 Sigmund Freud declared dreams to be “the royal road to the knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind”. Just three years later, William James wrote,

Our normal waking consciousness… is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different … No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.

William James ‘The Varieties of Religious Experience’ (1902)

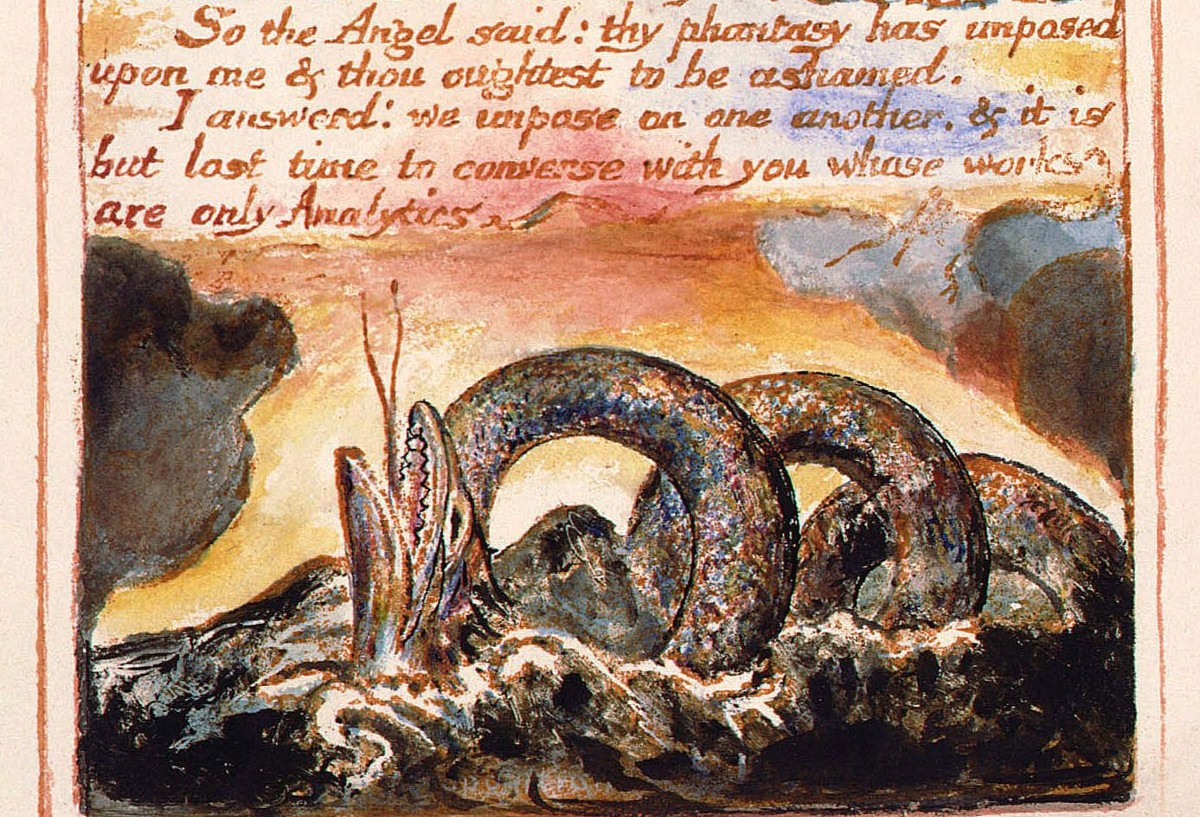

Psychotherapy adopted Freud’s method and dreamwork is fundamental to almost every therapeutic modality. James’s insight, on the other hand, has been ignored for over a century. His understanding was gained by self-experimentation by inhaling nitrous oxide, a mild psychedelic. Now, in 2023, the new frontier is psychedelic-assisted therapy, and once again, as with Freud’s dreams, we are looking to an altered state to bring us insight and healing. Even so, the acceptance of psychedelics as an adjunct to therapy – if it happens – will likely come without the acceptance of James’s insight that “normal waking consciousness … is but one special type of consciousness”. Dreams and psychedelics will be treated as ‘special’, exotic places to visit and perhaps bring back treasures or souvenirs to enhance normal waking awareness.

In contrast to this, the Weird Therapy project argues that navigating altered states of consciousness is a part of everyday life, and therefore also of psychotherapy.

We might not think of emotions as an altered state. Yet for people who are used to living in their thoughts, it can be profoundly transformative to begin to attend to the messages of their own emotional life. This is often what brings people to therapy.

A forgotten grief surfaces; you inconveniently fall in love with someone you shouldn’t; you have no energy to get out of bed one day and you’re diagnosed with depression; intrusive anger grabs you by the throat; you feel a melancholic longing for something unknown. These experiences come unbidden, as if from somewhere else, speaking a language that you can’t understand. You know, somehow, that you once understood it, and the question is how you ever came to forget.

Every therapist will be familiar with the experience of the client sinking into awareness of what has previously been hidden. The room grows quiet, or gets noisy; time and space soften their usual boundaries; spontaneous tears come. These are the signs of us entering an altered state together. In my own practice, I have come to believe that unless something like this occurs, nothing therapeutic will happen. It might sound like I’m being overly mystical, or else exaggerating the strangeness of what is an everyday occurrence. I believe that it is an everyday occurrence, but its strangeness is hidden from us by the hidden assumption of modernity that there is only one ‘real’ state of consciousness.

During my therapeutic training, I found that my clients were not staying with me for more than a few sessions. There was always a good reason, but my supervisor wisely said that something was wrong. She said, “do whatever it is you do to centre yourself before the client comes in”. I didn’t have such a practice, but I found myself putting one hand to my heart and one to my belly, and taking slow deep breaths. And that worked: the clients felt something different, and they stayed. To be fully present, I needed to anchor myself in my heart and my body, because my default place to be – the only place I felt fully safe – was in my head.

Even deeper and more primal than emotion is the inner felt sense, the somatic (bodily) experience of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). The ANS is responsible for most of the bodily processes that we are normally unaware of – blood circulation, digestion, most of our breathing – and also for primal threat responses. These manifest as experiences that we are all familiar with, yet which we rarely pay much attention to: constriction in the throat as we struggle to speak; a heavy chest; a churning stomach; nausea; or the blood running cold. Bodily sensations are the building blocks of emotion, and so different to our usual modes of cognition that it can take practice to even bring these occurrences into awareness. It’s not too much to describe this as, well, a new world, or perhaps better as a Lost World, a Land that Time Forgot, since it transports us back into our evolutionary past. (Often in the movies I’ve just invoked there’s a scientist or businessperson character whose role is to boggle at the impossibility of dinosaurs still living in the heart of a tropical island. That might be a good representation of how our ordinary consciousness reacts when faced with an intrusion from an altered state: stiff, bespectacled, rigid in its sophisticated, yet wrong, thinking.)

“It is like this. As a large fish moves between both banks, the nearer and the farther, so this person moves between both realms, the realm of dream and the realm where one is awake.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.3.18-19

“It is like this. As a hawk or an eagle, after flying around in the sky and getting tired, folds its wings and swoops down into the nest, so this person rushes into that realm where as he sleeps he has no desires and no dreams.”

A primary concern of the major Upanishads, composed in India between about 700 BCE and 200 CE, is with different states of consciousness. Many of the early discussions in these texts are about what their authors thought of as the three fundamental ‘realms’ – waking, dreaming, and dreamless sleep. Unlike in our modern culture, where waking awareness is the only ‘real’ awareness, in ancient India the three enjoyed an equal status. In one Upanishad, the waking state is called vaishvanara, “the world of all men”, that is, the world we commonly experience together. Dream meanwhile is understood in these texts as a largely private experience, but profoundly creative. Dreamless sleep, finally, in which consciousness merges with its objects of awareness, is described as one of pure bliss, ananda, and compared to the orgasmic unitive embrace of the beloved.

What the image of the fish, or of the eagle, suggests is that the person (purusha, the subjective spirit) is a traveller through different states, rather than being identified with this one state. Yet we need to be cautious here, too. The practice of ‘disidentification’, found in many spiritual traditions and some transpersonal psychotherapeutic modalities, can be a way to refine and strengthen the conventional perspective. “I am not this body, I am not these thoughts and feelings …” is, I would argue, exactly the wrong direction to go in, since it reifies (makes real) the mind and asserts its primacy over everything else. Retreating into the head, or into the spirit, is so often at the root of the problem we have.

My suggestion for aspiring Weird Therapists is that we seek to become amphibious, swimming, walking or flying through the worlds. This differs from therapeutic models in which we are more like divers exploring hidden depths with a supply of waking-consciousness air, or miners excavating the unconscious in search of treasures that we can bring back to the surface, or perhaps colonists plundering a ‘savage’ land of its gold. This is not only a therapeutic question, but also a philosophical one. If we assume that the ordinary waking consciousness of everyone is the reality, then of course any other world is, at best, an exotic holiday destination, and at worst a meaningless rubbish heap.

Amphibiousness suggests that different realms of experience have a broadly equal ontological status, and that our discomfort or confusion there is not so much an inherent quality of those places as it is of our unfamiliarity with them. A critic of this kind of approach might even say, ‘that way madness lies’. And perhaps that would be right: madness itself being a place that offers asylum, in which the psyche may survive something unbearable. If we want to help someone who has become mad, then we first need to join them in their madness, accepting that it does make sense in some way we have not yet understood. Madness deprives us of access to that vaishvanara, the shared reality of all; and in order to find our way back there it may be we need someone to join us in the place of imprisonment, offering companionship.

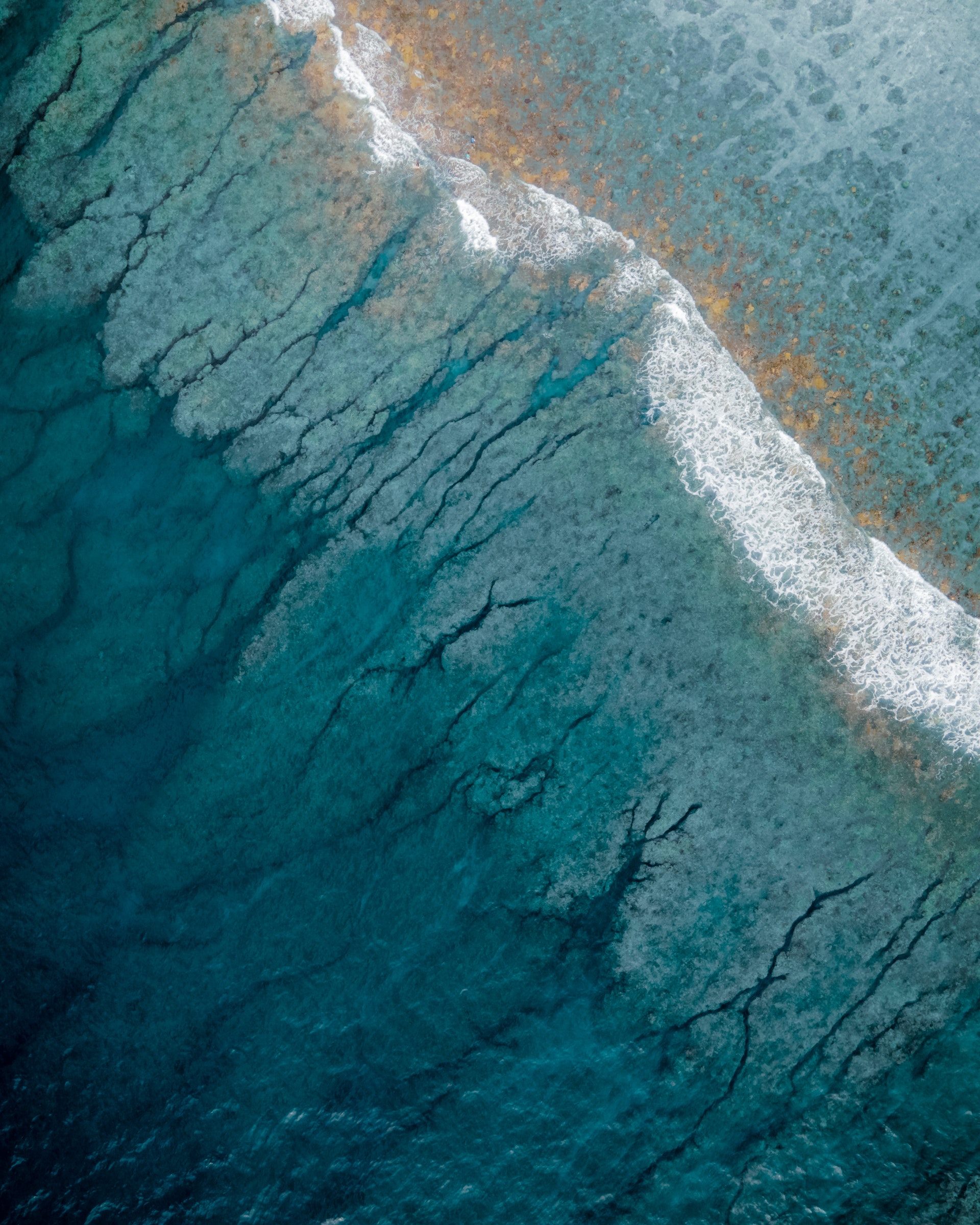

The term amphibious derives from Greek amphi + bios, meaning ‘both kinds of life’. Perhaps an even better image for the chromatic nature of consciousness is offered by Proteus, Greek water god of “elusive sea change” who could tell the future, but would change shape to avoid being caught and forced to do so. If we want to discover the precious key to healing, which is as difficult in its way as foretelling the future, then we need to be able to follow Proteus through his changes, becoming as fluid and mutable as he is.

Copyright © 2022 My Sunset by Bogdan Bendziukov.

1 thought on “Being Amphibious”

Comments are closed.