Here, I would like to examine more deeply the question of the weird, and its relationship to the uncanny, a concept allied to psychotherapy since Freud’s 1919 essay ‘Das Unheimliche’. Freud built on the work of Ernst Jentsch, who had published a paper in 1906 on the uncanny, using E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story ‘The Sandman’ to illustrate his argument. For Jentsch, the uncanny element in the story arose out of a confusion about whether a female doll in the story is really alive, or an automaton. For Freud, however, the truly uncanny element is the Sandman himself, a terrifying figure who tears out the eyes of children. The Sandman represents a repressed fear of castration, which returns to the narrator’s adult awareness to horrific effect.

Perhaps the definitive account of the weird is provided by Erik Davis in his wonderful book, ‘High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies’. Much of what I write in the next few paragraphs draws on Davis’s account.

The origins of the word are the Old English ‘wyrd’, describing “auguries, dooms, and the Fates as personified.” Urthyr, one of the Norns, Norse goddesses of Fate, is cognate with wyrd. From here, Scottish poets use “weird” to describe the Classical Fates before Shakespeare uses it for the witches in Macbeth (1605), his “weird sisters”. Yet in Shakespeare’s First Folio, he spells the word as weyrd, weyward, weyard; never as “weird”. It appears that the weird sisters have a double meaning for Shakespeare, both as oracles of fate, and as wayward, perverse and unnatural. This ambivalence is worthy of exploration.

We should submit ourselves to an

unknown fear

Shakespeare was a close contemporary of Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes, the founders of the scientific method and of modern philosophy. Already in Shakespeare’s time, there was a turn away from the old myths and from the supernatural. In ‘All’s Well That Ends Well’ (Act II, Scene 3), Lafeu comments on the view of the supernatural held by fashionable people at the dawn of the 17th Century:

They say miracles are past; and we have our philosophical persons, to make modern and familiar, things supernatural and causeless. Hence is it that we make trifles of terrors, ensconcing ourselves into seeming knowledge, when we should submit ourselves to an unknown fear.

Shakespeare expresses here both a keen awareness of then-current thinking, and an elegaic sense of a lost connection to the miraculous. Our “philosophical persons” may make trifles of actual terrors, hide in “seeming knowledge”, but – he seems to say – “we should submit ourselves to an unknown fear.” This last phrase could serve as a motto for the Weird Therapy project. The “should” is important; perhaps as a moral imperative to approach the numinous with a holy dread, or perhaps because it is simply better to acknowledge the immensity of what we do not know than to pretend to “seeming knowledge”.

In Shakespeare’s weird (or wayward) sisters, then, we find what Davis calls “the womb of the modern weird”. Whereas in earlier times, the wyrd meant the fundamental nature of reality, the Fate that even the gods could not avoid, for we moderns it takes on a different sense, that of something perverse, infantile, exiled and forgotten.

Freud would argue that this can be explained as a return of repressed infantile terrors; which is a way to make the Weird Sisters “modern and familar”. But the weird is not the uncanny. The critic Mark Fisher drew the crucial distinction in his book ‘The Weird and the Eerie’. As Davis writes, “Psychoanalysis explains the uncanny by referring to an inside: in particular, to the repressed inner dynamics of the family. This hermeneutic is what Fisher calls a ‘secular retreat from the outside.’ The weird, by contrast, does not belong at all.” Fisher writes that it “brings to the familiar something which ordinarily lies beyond it.”

Highbrow Uncanny, Lowbrow Weird

Perhaps due to its association with psychoanalysis, the uncanny has highbrow associations. When horror can be explained away through developmental roots, it gains an intellectual respectability that the weird never has. This is because the one who does the explaining, and by implication their readers, enjoys a superior intellectual position to those who suffer from these uncanny eruptions. The unheimlich offers us a homely interpretation, brings us back in to a consensus reality stripped of illusion, fantasy and the paranormal. The weird, by contrast, peers in at us from the outside, a thousand-eyed monster rendering us unrecognisable to ourselves.

Among the stories of the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, there are two that mirror each other: ‘The Aleph’ and ‘The Zahir’. In each, the narrator is a vain, envious literary snob who is in love with a glamorous woman, and who has a terrible brush with a miraculous object. The Aleph is a single point in space, discovered in the cellar of a house, in which everything in the world may be seen simultaneously. The Zahir is a small, ordinary coin that, once seen, can never be forgotten, and which inexorably takes over all thoughts. These extraordinary manifestations are so memorable that it is easy to miss how they connect to the biographies of their respective narrators. Aleph and Zahir are metaphysically opposite, at extreme ends of a spectrum of the incredible, and yet both link somehow to love, an emotion that, however commonplace in its origins, both elevates and destroys the narrator with an inhuman power. We read the story, and forget the tawdry romance (Jung remarks that the anima has poor taste) that precedes the fantastical element. Borges has not forgotten it, of course, and it is an aspect of his brilliance to make the reader forget, just as the narrator forgets, missing the trick that creates the uncanny ‘return of the repressed’, that something infantile that, in Freud’s phrase, “should have been surmounted”.

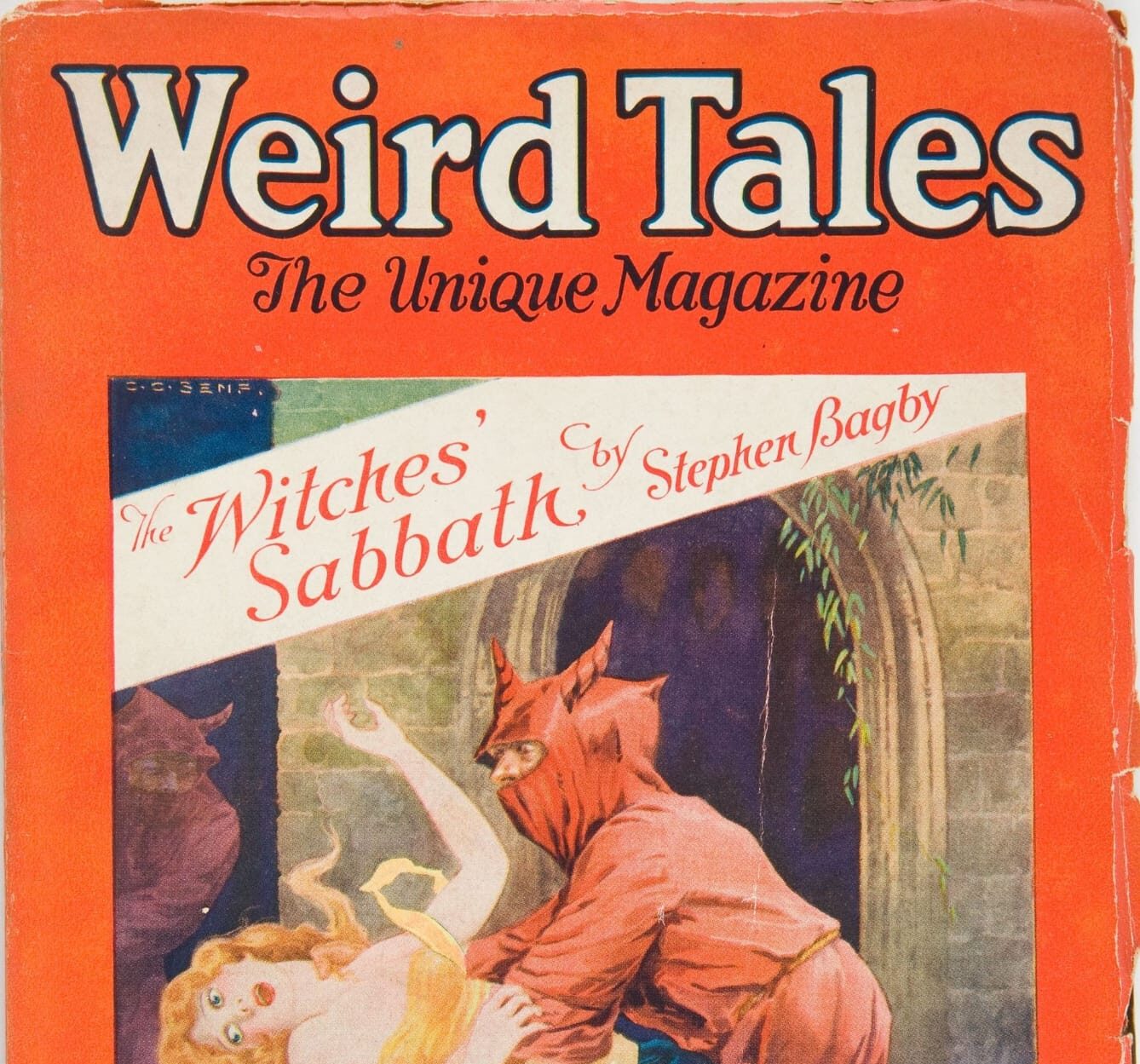

If Borges offers his readers the reassurance of an intellectual high ground from which to contemplate his fantasies, there are no such comforts in the weird. Here, at least in the Californian 1970s Davis writes about, we are in the realm of superstition, gonzo conspiracies, pulp magazines, delusions, psychedelic drugs, and horror thrills. Perhaps it is true for us that, as the weird science fiction writer Philip K Dick said, “the symbols of the divine show up first in the trash stratum.” Since the modern world has decided to banish anything ‘outside’ to the realm of the non-existent, it now shows itself in the speculative fiction of such disregarded genres as fantasy, SF, and horror.

In H.P. Lovecraft’s essay on supernatural horror and the weird tale, he writes,

The one test of the really weird is simply this—whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the universe’s utmost rim.

For Lovecraft, in other words, weird fiction can only succeed if creates a connection to the outside. It is perpetrated as a kind of hoax on the reader, who begins to wonder if it may somehow indeed be true. The thrill of horror that we feel in contemplating Cthulhu in his depths, the scream of Nyarlathotep, or the dreadful book of the Necronomicon, comes with a hoax-like quality. We mostly know these things are made-up. But they excite us tremendously, and it is in the suspension of rational processes that we connect to something vital and even delightful in ourselves. Borges is also famous for his literary hoaxes, of course, but as Fisher writes, “Lovecraft instantiates what Borges only ‘fabulates’; no one would ever believe that Pierre Menard’s version of Don Quixote exists outside Borges’ story, whereas more than a few readers have contacted the British Library asking for a copy of the Necronomicon.” It appears that we have a particular longing for the weird, for something that will break through from the outside, shatter the hermetic bubble of modernity with its self-satisfied illusion of total knowledge.

By offering an explanation for phenomena that do not seem to fit, such as madness, ghost hauntings, magickal events, Freudianism protects the boundary with the outside. We may not understand everything yet, it implies, but we will. Anything ‘paranormal’ is merely waiting its turn to be explained away.

Davis’s work offers a re-evaluation of the weird, as a refuge for what has been left out. Even if we are not entirely seduced by the work of his three heroes of weird fiction – Terence McKenna, Robert Anton Wilson and Philip K Dick – or by the American Weird in general, I think there is something of great value here.

In the past three years I’ve been getting to know more of the culture that surrounds the weird, through the work of Davis, and podcasts such as Weird Studies, the Secret History of Western Esotericism, and Occult Experiments in the Home. Although I have been describing the weird as somewhat lowbrow, these days it is the territory of serious thinkers. What I have found is that the weirdosphere is chock-full of often scarily bright people who for a variety of reasons now take a serious interest in alchemy, Tarot, I Ching, astrology, Chaos Magick, paranormal investigations, and UFOs. For these people, the ‘weird’ is not a badge of the counter-culture, or an affectation, but the gateway to those aspects of the real that modernity has made weird.

As the world hurtles towards ecological destruction on a number of simultaneous courses, we might do well to pause and ask what modernity may have got wrong.

In the next post, I will examine the therapeutic implications of the uncanny and the weird through an examination of the parallels between these concepts and those of The Labyrinth and the Maze.

Copyright © 2022 My Sunset by Bogdan Bendziukov.